History

Battle to Save East Housing

Renewed Hope Housing Advocates began in 1998, as an organizing effort of the Buena Vista United Methodist Church, long an activist church in Alameda. Vickie Smith, a member of the church’s community development committee, suggested a focus on the early stages of gentrification in the West End.

She had grown up in the old Navy housing projects on the West End and been through the fair housing battles of the 1960s and she began to notice people were leaving as rents were going up in the wake of the dot-com boom in digital technology.

For decades after World War II, the West End was defined by its relationship to the Alameda Naval Air Station, which had just closed in 1997. Here, low-income families and Navy families were mixed in with old-time residents while the rest of Alameda was marked by regal Victorians, lots of apartments, beautiful neighborhoods and a sort of guardedness about being across the estuary from Oakland and the desire to withstand its so-called “problems.”

The committee responded to Vickie Smith’s warning by recruiting West End residents and activists Jeanne Nader and Peggy Doherty. Lynette Lee, then director of the East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation and Rev. Michael Yoshii were also part of the committee. Peggy was also a member of St. Barnabas Catholic Church on the West End, which eventually lost one-third of its parishioners to rent displacement.

In that period, the East Housing, former Navy housing along Atlantic Avenue, was scheduled to be developed by Catellus Corporation and when the committee approached then-City Manager Jim Flint, he told them gentrification was coming to Alameda and there was nothing they could do about it.

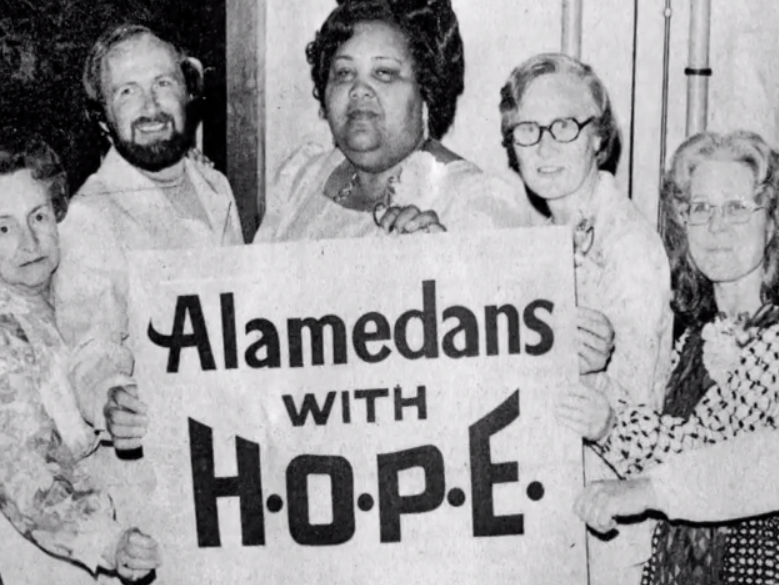

In response, the group decided to name itself Renewed Hope organize itself around a campaign to block this plan and promote the conversion of the Navy housing to affordable housing. It was drawing on and honoring the work the pre-existing housing advocacy group, Housing Opportunities Provided Equally (HOPE) that had closed up on the early 90’s.

With the help of a hired community organizer Cynthia Okayama Dopke, Renewed Hope mobilized a large group of people of all races, largely from the West End, starting with an interfaith witness held at the gates of the former naval base housing, and moving on to staging marches, turning out crowds at council hearings and holding candidates forums for the 1998 elections.

The activists saw an opportunity to link the displacement directly to a cause — the overheated market, which they could tell would soon collapse. And they had a solution they could offer: Instead of building hundreds of new expensive homes, why not save the housing that’s there and — renovate it as affordable family housing? The houses were largely three- and four-bedroom units and could have been rehabilitated and sold, at the time, for between $125,000 and $160,000. The rental units would have ranged from $700 a month for two bedrooms to $1,350 for four bedrooms.

This effort to rehab existing housing was crucial because Measure A, passed in 1973 to stop the destruction of Victorians, blocked the development of new multi-family projects.

Lynette’s EBALDC team prepared an alternative proposal for financing the renovation work. The term “workforce” housing came into use because Renewed Hope wanted to show that cost of housing was becoming too high for people with regular jobs and decent incomes and that many were renters who would love to be homeowners.

Alameda, by the way, is about 50 percent renters. The city often used this fact as proof that it already had enough affordable housing.

Renewed Hope argued that affordable housing was something everyone in Alameda would benefit from. The council was told “our children can’t afford to live here; people of average incomes such as teachers and firefighters can no longer afford to live here; losing families is bad for school funding.”

The city council was very committed to the notion that the mostly white, middle class homeowners in town was its only real constituency. Renewed Hope supporters often faced a well-organized opposition made of people who supported Measure A, whose message was “we are the real Alameda” and “if you can’t afford to live here you should leave.”

The city went ahead with plans to tear down these homes and construct 485 large new homes, now known as Bayport, but 48 homes for moderate income homeowners – roughly in the $60,000 range for a family of four in 2000 – were included, as required by state redevelopment law.

Despite the splendid organizing, the battle was lost. It wasn’t the time to prevail, but Renewed Hope did restart a debate that was cut off in the early 1970s. And that was: Who deserves to live in Alameda?

For the next 15 years, the group — under presidents Tom Matthews (who died in 2007) and later, Laura Thomas — would deconstruct and reconstruct the idea of what affordable housing could be and whom it should serve.

Alameda Point lawsuit

Left with a small, but dedicated steering committee and some loyal supporters, Renewed Hope in 2000 began to focus on the Naval Air Station site because it would bring a developable land mass that was half again the size of Alameda into the city, and it was in the West End, locus of the East Housing struggle.

Eve Bach of Arc Ecology, a non-profit organization that worked on base closure issues, had joined the RH steering committee and she persuaded members to sue the city based on an inadequate EIR done by the Navy in approving the Catellus development. That was the pretense. The aim was to demand an affordable housing mandate for the base and RH won a settlement agreement calling for 25 percent affordable housing. It also won Catellus’ commitment to providing land and funding for a 62-unit project of both rental and homeownership units, the Breakers, which opened in 2006.

Measure A

We had won our bid for a bigger portion of affordable housing, but the Measure A multi-family housing ban meant developers would be forced to build affordable housing that was all detached single family or duplexes, an expensive proposition for them.

And, sure enough, for more than a decade Measure A was one of the big reasons development at Alameda Point didn’t get off the ground.

The steering committee spent many years presenting the argument for multi-family housing and against Measure A, which was the subject of a 2008 public forum.

Generally the city balked at bringing this problem out for public discussion and continued to expect prospective developers to solve the problem for them.

During the same period, Renewed Hope pushed the city to adopt an inclusionary ordinance calling for developers to build 15 percent affordable units as part of a project rather than donate funds to the city’s affordable housing program, which was seen as a way for the city to spend money on insignificant homeownership subsidies.

Harbor Island Evictions

Along the way, the housing situation for low income folks became worse when a Florida investment group, the 15 Group, purchased the Harbor Island Apartments, a 615-unit set of buildings that housed many Sec. 8 voucher holders and had been built with a federal subsidy. In 2004, the 15 Group, which had allowed the buildings to deteriorate, announced it would be evicting everyone to make way for renovation and upgrading.

Renewed Hope joined in the fight with legal and policy support, but the 15 Group got its way and Alameda lost a good portion of its Black population and took a $5 million hit to school district revenues with the loss of 300 children who were attending school.

Measure B

In 2010, the developer Sun-Cal attempted to clear the way for developing Alameda Point by qualifying an initiative to overturn Measure A and make building multi-family dwellings easier. Unfortunately, it also included the Disposition and Development Agreement as part of the initiative and Eve Bach’s analysis showed the DDA was a bad deal for the city. Renewed Hope felt compelled to oppose the initiative since it gave far too much power to the developer. In so doing, RH demonstrated it sided with the interests of the city over developers. Measure B lost by a landslide.

Housing Element Victory

Renewed Hope began rather cautiously to focus on using the Housing Element as another pressure tactic. Eve Bach had been bringing it up time and again, reminding us of the state mandate that each city to have a valid element in place, in which it had to demonstrate adequate sites were available and that there were no impediments to building affordable housing. The city had adopted an element for the 2001-2006 period, but it relied chiefly on unavailable Navy base sites and continued to assert that Measure A wouldn’t stifle the developers’ ability to finance affordable housing. RH sent a strong critique of the element to the state Housing and Community Development Department which used it to refuse to certify the city’s element.

Left in limbo by the lack of direct sanctions against scofflaw cities in Housing Element law, the steering committee began to realize the base development was really stymied by Measure A and for affordable housing in Alameda to get off the ground, it had no choice left but to file a lawsuit over the lack of an element.

At the time Urban Habitat and Public Advocates were suing the city of Pleasanton and the success of that helped to bring the group around. It was evident how much power RH could wield doing the same. At the same time, state policies under SB 375 (designed to address greenhouse gases) were starting to put more pressure on cities to get certified elements.

In the meantime, the makeup of the council changed to embrace a more sympathetic understanding of affordable housing from a standpoint of social justice and community stability.

It became clear they were well aware they were vulnerable to a suit and would appreciate the political cover a threatened lawsuit would give them to embrace the housing element.

Eve died of cancer in early 2010 but before that she introduced the steering committee to people at East Bay Housing Organizations and Public Advocates and with them we gained some really important allies in taking on our decision to press a lawsuit.

As individuals, we felt somewhat vulnerable, knowing we could be seen as people who were attacking the integrity of our city and knowing we had support, even outside Alameda really gave us energy and — resolve.

The minute we began to rattle our swords – we sent the city a demand letter – they swung into action. The City planner Andrew Thomas came to the council and planning board with a time table which pretty much matched the one we demanded. City Manager John Russo was in support as well. It was fall 2011 and it needed to be done well before the new period ensued in 2014.

In the spring of 2012 with the aid of attorneys from the Public Interest Law Project in Oakland and Public Advocates in San Francisco, RH, and city staff drew up the city’s draft Housing Element for 2007-2014.

Unable to use sites on the base, which was not in city hands, most of the sites were in Alameda’s northern waterfront, near the Estuary and towards the West End. Most of the rest of the town, where there might have been more opposition had no sites left.

Our biggest challenge was creating some real incentives for developers to build affordable housing. The housing element law sets a fairly low rate of 30 units per acre as standard for affordability. If a developer meets this minimum, but creates no affordable units, the state is satisfied.

We worried that 30 units an acre wouldn’t attract a developer who would be able to finance the addition of affordable units, and we knew that greater densities could set off some major opposition.

Since we were asking the city of Alameda to override its charter amendment against multi-family housing to adopt an element in compliance with state law — we were stuck at this point.

To get past this limitation, we created overlay zones where 30 units was the standard but if a developer was interested in doing at least 50 percent affordable, he or she could use the state density bonus to boost it to 40 units per acre.

By applying this zoning to about half the sites designated, the city was able to reach its required Regional Housing Needs Assessment numbers (the amount of housing assigned to it by the Association of Bay Area Governments).

The council happily, even joyfully, passed the element in July 2012 even as the last pro-Measure A member trying to rally their supporters, but could not muster many people. They seemed to have lost steam, while Renewed Hope never gave up.

The latest Bay Area housing crisis has only made the need for affordable housing more important. In addition it has created a greater acceptance for it among Alameda’s rank-and-file citizenry. The struggle between the desire to keep Alameda a livable community for SOME and a livable community for ALL hinges, in part, on housing and transportation issues. But it actually requires everyone’s acknowledgement of what makes a community whole beyond good schools and neatly tended building facades.

As a group we have triumphed in changing city policy, but we hope to build something more.

Many of the original Renewed Hope supporters were people of faith who were moved by Martin Luther King’s belief in a beloved community where reconciliation and redemption are found. It is something many of us want for Alameda along with housing justice and security, a place where compassion and solidarity thrives.

Will you join us?